When director Paul Thomas announced that he was returning to Behind the Green Door—the 1972 film that made Marilyn Chambers a symbol of liberated erotic cinema; many assumed it would be a nostalgia exercise. Instead, he delivered something closer to a requiem. The New Behind the Green Door (2013) does not simply repeat the original’s masked orgies or 1970s decadence; it meditates on what happens when desire becomes a way of remembering.

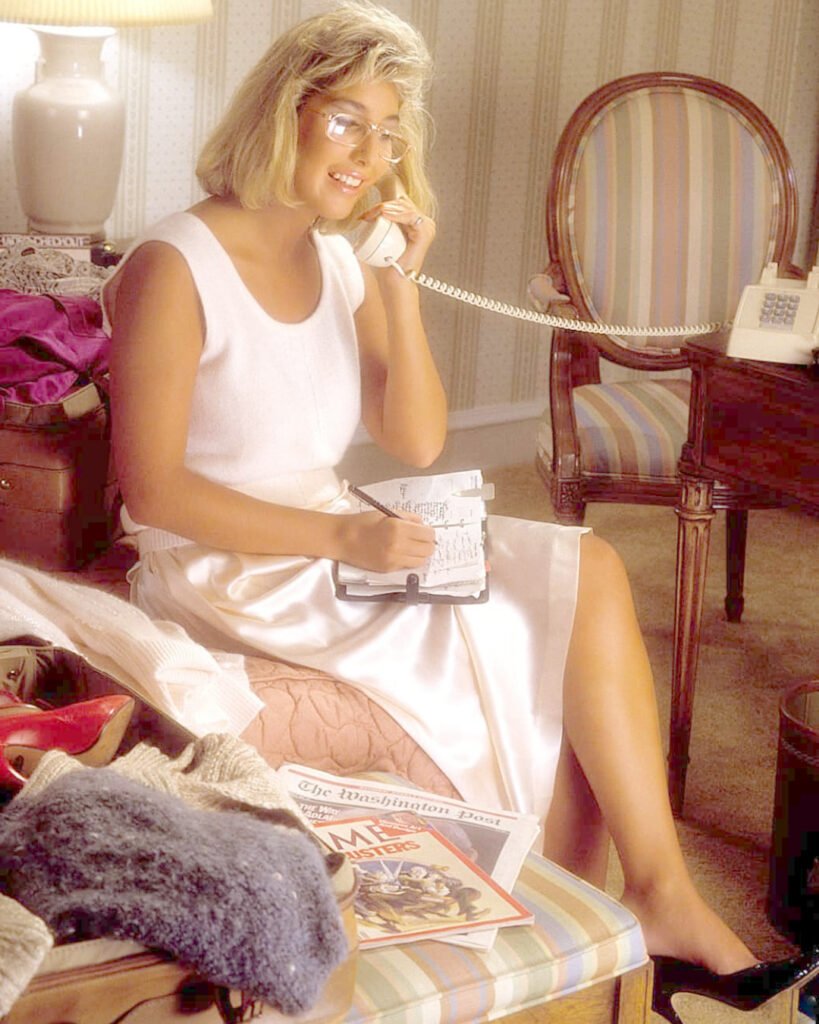

At its center stands Hope, played by Brooklyn Lee, a drifter who arrives in San Francisco stripped of money, identity, and certainty. She is a woman moving through the ruins of a life and the remnants of a cinematic legend. The film’s narrative half noir, half psychological fable follows her descent into a world where erotic ritual becomes a mirror for loss and self-reclamation.

Thomas’s camera lingers on reflections, glass panes, and half-lit corridors. His San Francisco is not the neon carnival of the 1970s but a bruised modern city: fog curling around streetlamps, rain glossing the windows of diners, subway grates exhaling steam. When Hope first appears, she is framed against a dark storefront window that doubles her image a visual signature that will repeat until the film’s final shot. The double is important: Hope is never only herself. She is the daughter of a mystery, the echo of a performer from another age, and the reincarnation of an archetype—woman as both muse and witness of her own desire.

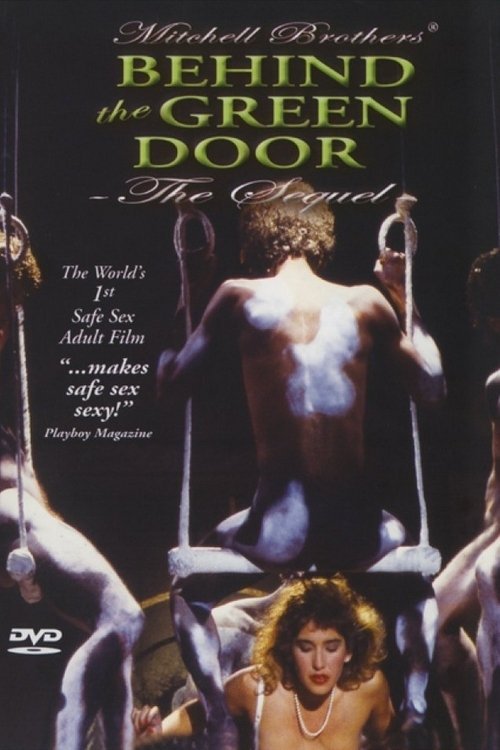

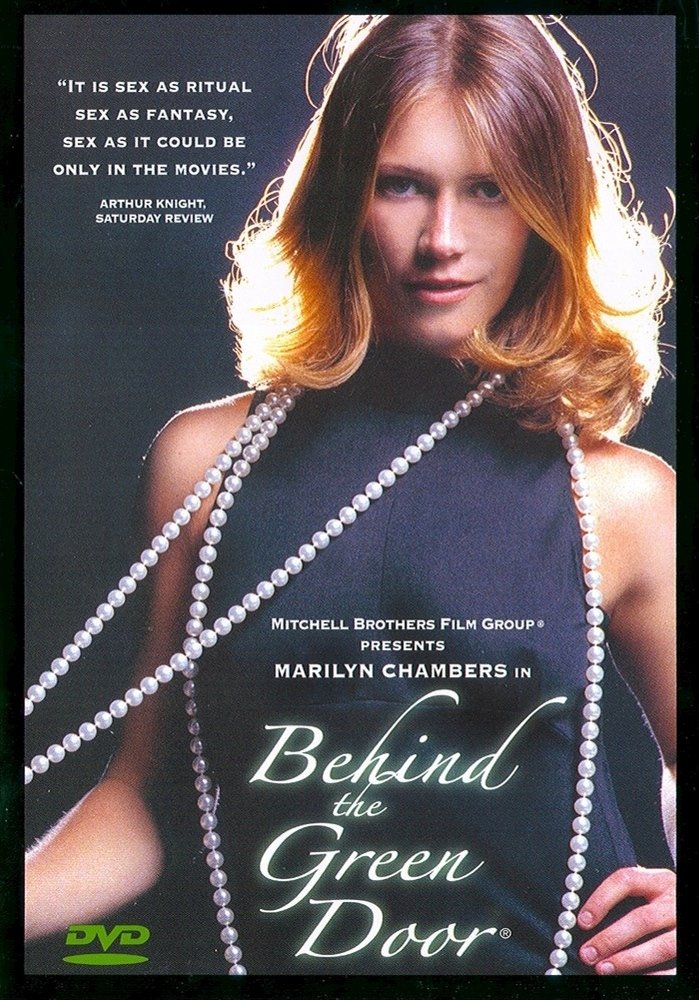

The Lineage of the Door

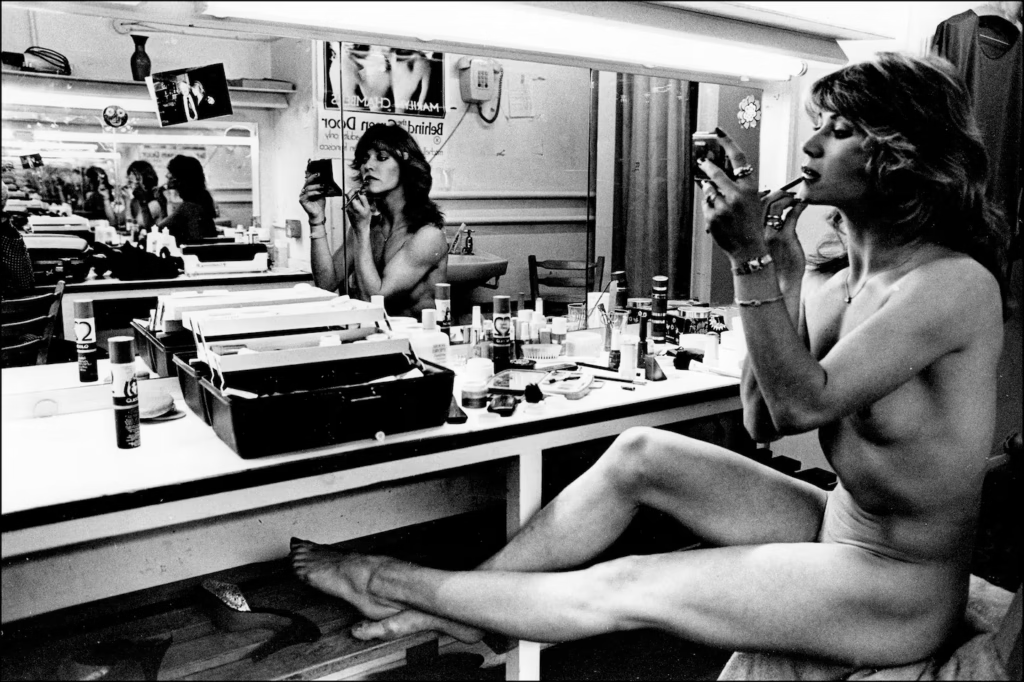

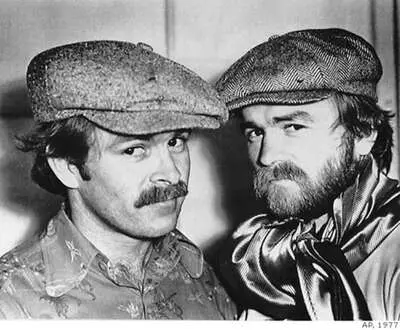

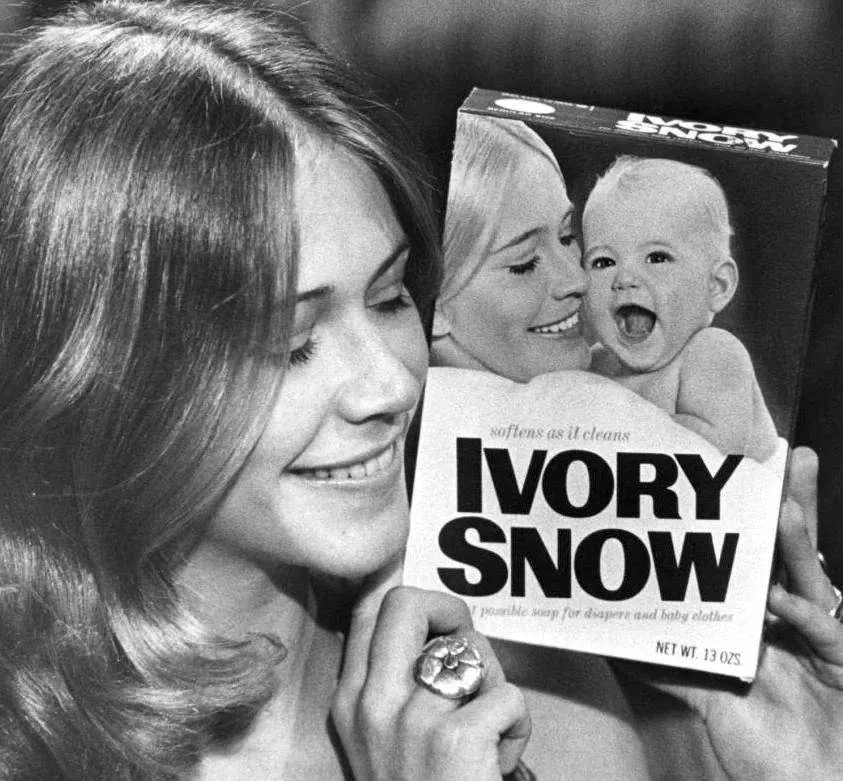

The original Behind the Green Door was, at its core, an experiment. The Mitchell Brothers took the theatrical excess of early 1970s San Francisco and fused it with silent-film surrealism: masked audiences, ritual staging, an interracial climax that was revolutionary for its time. In that film, Gloria Saunders—played by Marilyn Chambers—was kidnapped, displayed, and transformed into an object of collective fantasy.

Forty years later, Thomas inverts the premise. His heroine is not abducted but drawn by curiosity. Hope chooses to cross the threshold. The story becomes a question of agency: what does liberation mean when the body itself is currency, memory, and confession?

Thomas, who came of age directing adult features during the VHS era, has described the remake as “a letter to the ghosts of erotic cinema.” In interviews he lamented how modern pornography “forgot how to be uncomfortable in beautiful ways.” He wanted to restore ambiguity; the uncomfortable intimacy between performer and viewer that once made the genre dangerous and alive.

From its first frames, The New Behind the Green Door plays like a fevered travelogue through a city of mirrors. Hope wanders beneath bridges, sleeps in doorways, and clutches a weathered photograph she believes holds a clue to her parentage. Her boyfriend, James (James Deen), is equally adrift part lover, part parasite. Their scenes together are tender but raw, filmed in long takes that capture the exhaustion of people loving each other as a way to stay alive.

Thomas edits their embraces against flashes of memory: birthday candles, motel corridors, fragments of laughter. The technique blurs time, suggesting that every act of touch carries the residue of all that came before. The film’s score ambient strings layered with faint industrial noise—turns intimacy into a haunting.

The Inheritance of Desire

Early reviewers for AVN and XBIZ called the film “a neo-noir confessional of desire,” and it is exactly that. The mystery is not who Hope’s parents are but what she has inherited from them:

the compulsion to seek transcendence through exhibition, to dissolve shame by being seen.

When she learns that her late mother may have been connected to a cult-like underground performance group, the story’s mythic arc begins.

Thomas and cinematographer Eddie Powell use chiaroscuro light to make every interior look like a confession booth. The camera hovers as if overhearing secrets. Every room feels temporary, as though borrowed from another life. When Hope first glimpses the fabled green door—a velvet-draped entrance hidden behind a jazz stage it is less a portal than a memory returning.

The Cast as Co-Authors

What makes the film remarkable is the way its performers speak about it. Brooklyn Lee said in an XBIZ TV interview that playing Hope was “an emotional excavation more than a performance.” She auditioned multiple times and described feeling that the role “was supposed to be mine.” On set, she insisted that each scene be treated as dialogue, not choreography. The exhaustion visible in the climactic sequences was real; she filmed them over two days with minimal breaks, using fatigue as texture.

Director Paul Thomas guided this process like a therapist more than a traditional filmmaker. Crew members later recalled that he began each day by asking the actors what they wanted the scene to mean. “It was never about fantasy,” Lee explained, “but about what lies beneath fantasy.”

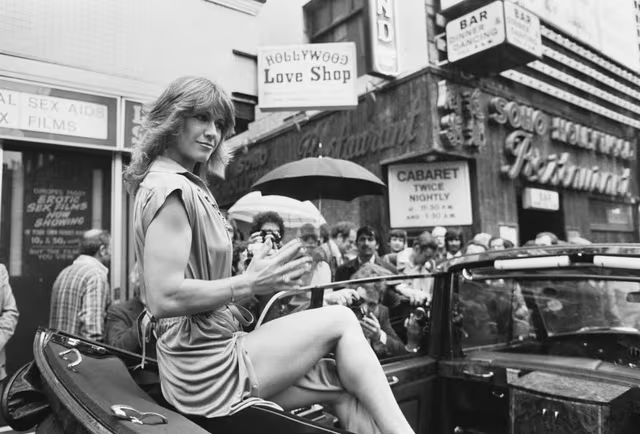

Also present was McKenna Taylor, daughter of Marilyn Chambers. Her participation gave the production an uncanny symmetry. “It felt like walking through my mother’s ghost,” she said in a Radar Online interview. Taylor appears briefly in the film but her presence lingers an embodied connection between two eras of erotic storytelling.

Finally, Johnnie Keyes, the original film’s trailblazing male lead, appears in archival footage and a cameo. At seventy, he described the experience as “seeing freedom reborn through awareness.” His inclusion roots the film’s mythos in living memory, turning what could have been a simple remake into a generational conversation.

Re-Opening the Door

By the time the green door itself finally opens midway through the film the audience understands it as both literal and symbolic. It represents the boundary between repression and revelation, anonymity and identity, the self that performs and the self that watches. Thomas films the threshold in slow motion: a curtain rippling, a sound like wind through pipes, a sudden wash of emerald light.

From that point onward, the narrative becomes a descent not into debauchery but into psyche. Each sequence within the club functions as a rite of passage. The performers who guide Hope through the experience played by Chanel Preston, Nat Turnher, Jon Jon, and Prince Yahshua embody aspects of temptation, memory, and forgiveness. The choreography is ritualistic, not explicit: movements suggesting surrender, communion, and rebirth.

Thomas cross-cuts these moments with archival imagery from the 1972 film, dissolving decades into a single cinematic bloodstream. The effect is disorienting and hypnotic; it asks viewers to see the erotic not as spectacle but as continuity a conversation between generations of bodies and cameras.

More than anything, The New Behind the Green Door is about the act of looking: how we see others, how we wish to be seen, and how the gaze itself can wound or heal. Hope’s journey becomes a meditation on spectatorship. The masked audience inside the club mirrors the film’s own viewers, implicating everyone in the cycle of desire and judgment.

In this way, Thomas transforms an adult film into a study of cinema itself. His style recalls Bergman’s confessional close-ups and Lynch’s dream logic as much as it does classic erotica. Every visual choice, mirrors, masks, repetition of color reminds us that eroticism is a language of seeing.

Descent into the Mirror: Scenes

Scene 1: Brooklyn Lee and James Deen – “What Remains Between Us”

Set against the backdrop of a cold Christmas morning in a run-down apartment, this scene captures the waning heartbeat of a relationship running on memory and inertia.

Hope (Brooklyn Lee) and James (James Deen) exchange modest gifts—hers thoughtful, his predictably provocative. He gives her a new vibrator, joking, avoiding eye contact. She smiles, but her eyes are searching elsewhere.

What follows is not a conventional love scene. It is quiet, reflective, and haunted. Hope uses the gift as James begins to speak aloud one of his fantasies—featuring Hope, other women, and his own imagined sexual power. Their bodies move, but their minds are elsewhere.

The scene is deliberately intercut with grainy footage from the original 1972 Behind the Green Door, blurring past and present. As Hope performs oral on James, the camera lingers not on explicit detail but on facial expression: hers focused, his detached.

When James finishes, abruptly and on his own terms, Hope stares at him in stunned silence. Her line—“What the fuck?”—isn’t just comic punctuation. It’s an emotional slap. Not because of where he finished, but because of how little she felt.

This scene establishes the emotional fracture that underpins the film: a woman whose body is on camera but whose orgasm, like her story, is deferred.

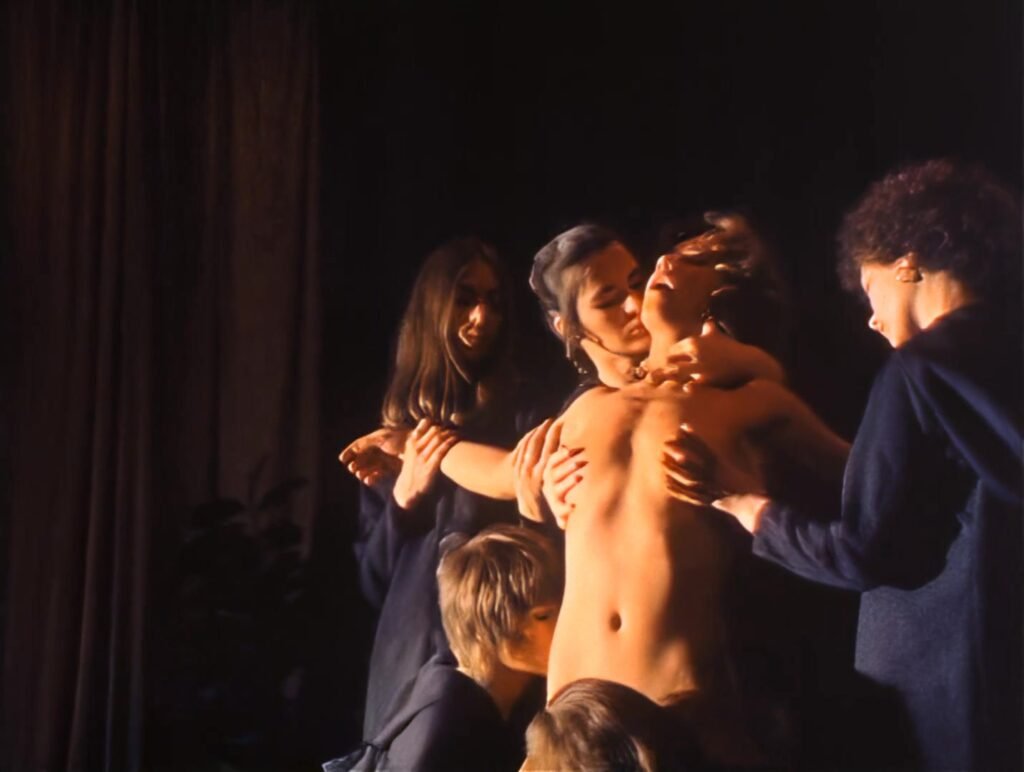

Scene 2: Dana DeArmond and Steven St. Croix – “The Ritual Begins”

At the Caligula Club, desire becomes performance—and Dana DeArmond knows the stage better than most.

In this scene, Dana’s character leads Steven St. Croix into a shower, the steam creating a veil between reality and performance. What unfolds is less passion and more ceremony: teasing, touching, and gradually building control.

The chemistry here is sophisticated, almost formal. St. Croix kneels; DeArmond guides. Their interaction is fluid, exchanging roles of dominance and submission, body and gaze.

Though the scene eventually moves to a bed and shifts into anal play, its most powerful moment is not penetration, but anticipation—St. Croix’s hand between DeArmond’s legs, the camera tightening its frame as her reactions shift from playful to primal.

Intercut between the ongoing masked party upstairs and Hope’s movements in the club, this scene functions as a thematic overture—introducing viewers to the power dynamics that drive the film’s erotic vocabulary.

Scene 3: James Deen, Ash Hollywood, and Penny Pax – “Fantasy on Replay”

A flashback within a fantasy, this brief threesome is James Deen’s imagined escape from the emotional landscape he shares with Hope.

Ash Hollywood and Penny Pax are portrayed as idealized versions of pleasure—eager, playful, perfect. In contrast to his interactions with Hope, James appears completely in control here.

The scene itself is brief, focusing mostly on oral play. It’s intercut with earlier dialogue where James had described this fantasy to Hope in intimate detail. What plays out on screen, however, falls short of that promise—perhaps by design.

When James climaxes and the women giggle, there’s a hollowness to the aftermath. No resolution. No completion. Just a man chasing the thrill of control without confronting the emptiness that follows.

It’s a dream scene, but one that reveals more about his insecurities than his desires.

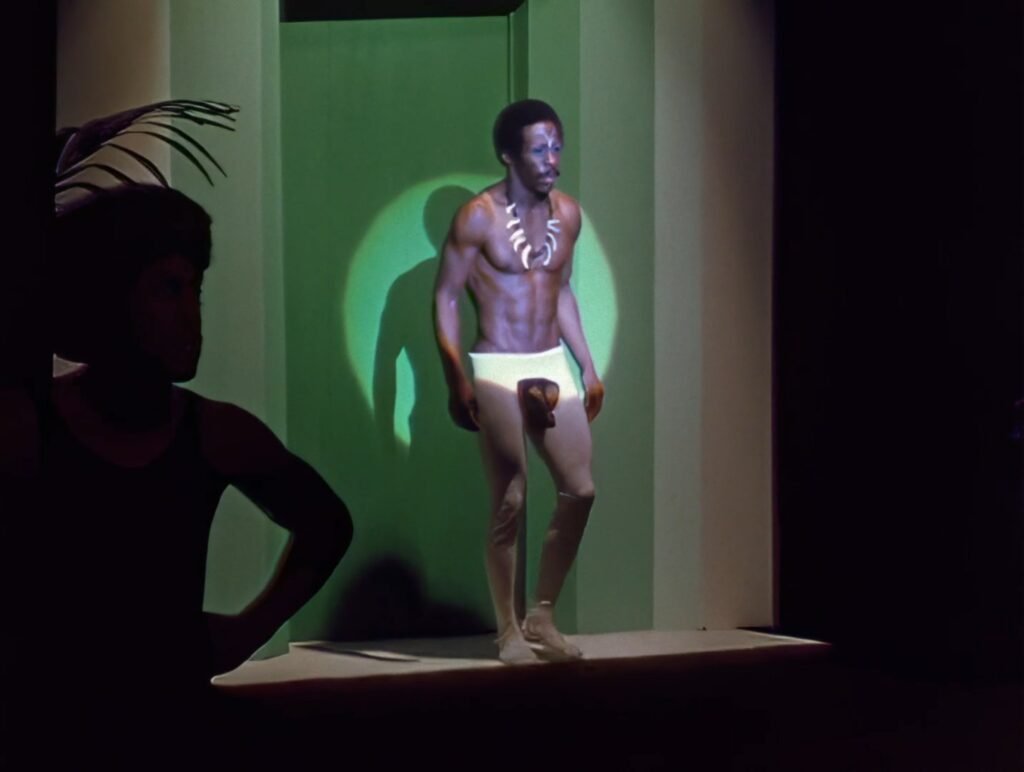

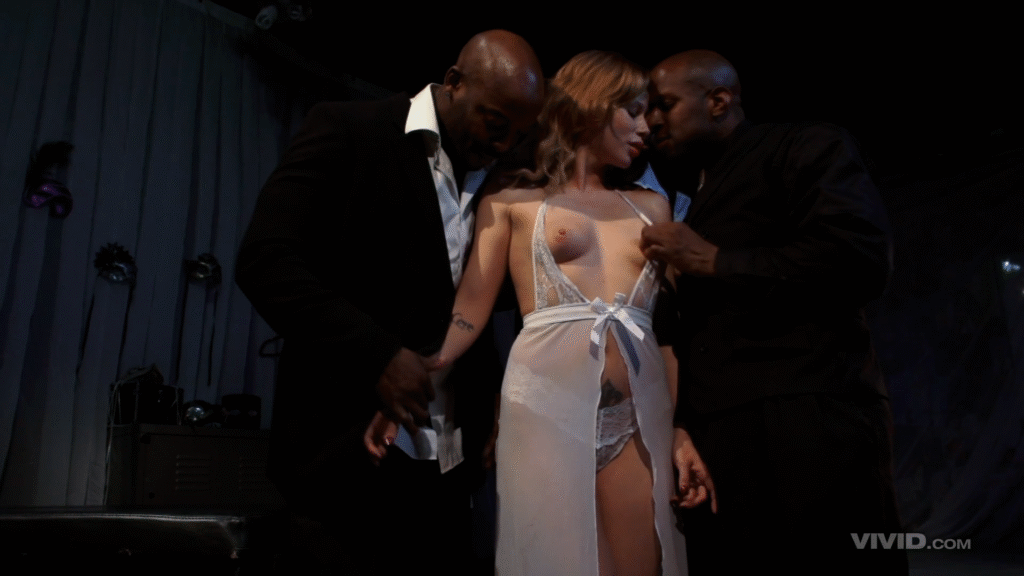

Sex Scene 4: Brooklyn Lee, Nat Turnher, Jon Jon, and Prince Yahshua – “The Ceremony”

This is the heart of the film—the moment where the myth and the woman meet.

After crossing through the green curtain, Hope enters the club’s central chamber, bathed in emerald light. She stands alone before an audience of masked voyeurs, as three male performers emerge—Nat Turnher, Jon Jon, and Prince Yahshua—representing strength, reflection, and transcendence.

What follows is not simply group sex—it’s choreography. A ritual. A sensual initiation. The performers do not overwhelm her; they engage her, honor her. The transitions between them are smooth, synchronized, mutual.

Hope’s expressions—pleasure, release, near-tears—carry the emotional weight of her entire journey. It is here, not in dialogue, that her reclamation takes place.

Interspersed throughout the scene are two smaller vignettes, one involving Chanel Preston, who guides another woman through a mirrored ritual, and one featuring performers in white masks echoing Gloria’s original performance in the 1972 film.

In the background, the original Behind the Green Door plays on a large screen, occasionally syncing shot-for-shot with Brooklyn’s scene. It’s not mimicry—it’s echo. A legacy.

This is not just the best scene of the film—it is the film.

Sex Scene 5: Brandy Aniston and Richie Calhoun – “The Detour”

Late in the story, after Hope’s rite is complete, we return to Richie Calhoun—this time in bed with Brandy Aniston, a performer who hasn’t appeared in the narrative until now.

The sex is energetic and well-performed. Brandy Aniston is present, expressive, and confident. Richie is charming, giving, and engaged.

But in the context of the film’s story arc, the scene feels disconnected. It takes place after Hope’s ceremonial transformation, breaking narrative momentum and emotional cohesion.

It’s as though the film is unsure whether it’s ready to let go of Richie’s character—and so it gives him a final indulgence.

Still, as a standalone scene, it’s effective. But as part of the narrative fabric, it tugs loose a thread that had already been tied off.

—Marilyn Chambers smiling faintly—as if both women share the same exit.

Final Interlude: Hope and Herschel – The Mirror Stage

There is one final moment—unspoken, dimly lit—between Brooklyn Lee and Herschel Savage. It’s not a sex scene, but it holds erotic tension in its stillness.

She sits, partially unclothed, in a room with no furniture. He stands by the door, speaking in slow riddles. His words land like prophecy, or maybe memory.

The camera lingers on Hope’s face as she listens, unmoving. It’s as though she’s hearing echoes not from him—but from her mother, from Gloria, from every woman who stepped behind a green curtain and came out changed.

Epilogue: After the Ritual

Hope walks into the dawn alone. Her steps are slow but steady. She is no longer searching—she is returning. To herself.

The erotic sequences that unfolded weren’t detours. They were keys. Each one unlocked a new understanding—of her power, her past, her desire.

This wasn’t a film about sex. It was a film about choosing to be seen.

Behind the Scenes: Vulnerability as Craft

On set, the atmosphere was reportedly closer to a theater troupe than an adult production. Crew members recalled long discussions about symbolism, lighting, and consent. Paul Thomas demanded that every performer understand the emotional stakes of each gesture.

Lee’s physical exhaustion during the Green Door sequence was authentic. She filmed late into the night, refusing body doubles or shortcuts. “We were shooting emotion, not anatomy,” she told XBIZ.

McKenna Taylor’s presence added spiritual weight. In interviews, she admitted she sometimes cried between takes: “It was like saying goodbye to my mother again, but also thanking her.”

Johnnie Keyes’ cameo required him to sit in silence for hours, watching the ritual unfold. When asked later what he felt, he said, “Peace. Like the conversation was finally finished.”

Symbolism of the Door

The Green Door itself, across both films, has come to represent the boundary between repression and liberation. In Thomas’s version, its meaning multiplies:

- Psychological – the threshold of self-awareness

- Feminine – reclaiming agency in a genre historically defined by objectification

- Cinematic – a portal between eras, celluloid and digital, fantasy and realism

The color green—once a marker of voyeuristic fantasy—becomes emblem of rebirth. Every time it appears, from the party lighting to Hope’s final dawn, it signals transformation.

Critical Echoes

After release, critics split between those expecting erotic spectacle and those recognizing a psychological film disguised as one.

Adult DVD Talk called it “a bold refusal of pornography’s usual grammar.”

XBIZ named it “a neo-noir confession where pleasure is language and pain is punctuation.”

For many, the film marked Brooklyn Lee’s artistic peak. It won her the 2013 AVN Award for Best Actress, an honor she dedicated to “every woman who ever felt split between body and soul.”

Paul Thomas soon retired from directing. In later interviews he referred to The New Behind the Green Door as “my eulogy for mystery.”

Behind The Craft, the Themes, and the Legacy

Paul Thomas’s The New Behind the Green Door is, first and foremost, an act of craftsmanship. Every frame feels deliberate lit, composed, and cut with the precision of someone building a cinematic ritual rather than shooting an adult feature.

The cinematographer, Eddie Powell, uses three primary palettes to track Hope’s evolution:

- Blue-grays dominate the first act, representing despair and anonymity.

- Gold and crimson fill the middle—the world of temptation, parties, and deceit.

- Emerald and silver define the club sequences, marking transcendence and rebirth.

The lighting design is painterly, recalling chiaroscuro masters like Caravaggio and Vermeer. Every source of illumination has narrative meaning: a lamp signifying safety, a spotlight representing judgment, the morning sun promising clarity.

Thomas and Powell filmed largely on digital RED cameras but used vintage 1970s diffusion lenses. The result is a texture halfway between film and digital—an intentional bridge between eras. “We wanted the movie to look like a dream remembering itself,” Powell said in an XBIZ production note.

The editing employs rhythmic breathing—long still shots punctuated by jolting cuts, mirroring the psychological tempo of repression and release. Viewers unfamiliar with adult cinema’s visual grammar might mistake it for an arthouse experiment; indeed, Thomas frequently cited Last Tango in Paris and Persona as tonal references.

The sound design completes the confession. Ambient hums replace conventional scoring. In key moments, we hear muffled voices through walls or the hiss of rain on metal, turning background noise into emotional commentary. When the ritual sequence begins, a single sustained cello note vibrates through the soundscape, threading all sensations into one pulse.

This craft transforms erotic narrative into cinematic meditation. Even without explicit display, the viewer feels intimacy—through pacing, breath, and silence.

At its core, The New Behind the Green Door is a film about the body as both site of trauma and instrument of truth.

Hope’s journey is structured like a ritual initiation:

- She begins nameless and impoverished—stripped of context.

- She enters the world of masks, learning to see the self as something performable.

- She finally reclaims her identity through conscious display.

This movement transforms objectification into authorship. Where the 1972 Behind the Green Door turned Gloria into a silent icon for male desire, Thomas gives Hope speech, agency, and motive. She chooses her exposure, making the camera her confessional rather than her cage.

Every act of desire in the film doubles as an act of remembering. When Hope enters the club, she is not discovering lust but recovering lineage. The erotic becomes historical—an inherited language of expression passed from mother to daughter.

Paul Thomas once said, “We all inherit someone’s silence.” Hope’s initiation breaks that silence; she voices what her mother’s generation could only perform.

The audience in the Caligula Club mirrors us, the real viewers. They are masked, anonymous, complicit. Thomas uses this device to ask: What is the cost of watching?

When Johnnie Keyes appears among them, his unmasked gaze redefines the act of looking. It’s no longer voyeurism; it’s witnessing. He becomes the elder seeing the next generation claim the narrative.

The difference between voyeurism and empathy, Thomas suggests, lies in intention—whether we watch to possess or to understand.

Critics often call this film a feminist remake, but Thomas resisted labels. He preferred the term “reclamation.” By allowing Hope to choose her path through the door, he reframed submission as strength.

Brooklyn Lee explained it perfectly: “Hope isn’t rescued or punished. She just stops being afraid of what she wants.”

This subtle distinction changes the meaning of erotic cinema itself—from spectacle to introspection.

Voices from Within the Production

Behind every shot, there was conversation—about meaning, boundaries, and the emotional truth of performance.

Brooklyn Lee, who retired from the industry soon after this film, later reflected that it had “closed a chapter of my life.” She said the role allowed her to explore vulnerability without shame:

“It wasn’t about fantasy—it was about finding the line between acting and feeling, and realizing they’re the same.”

Paul Thomas treated the set as a sacred space. Crew members recalled that before filming the central sequence, he asked everyone to stand in silence for a minute, “to remember why art matters.” He told the performers, “The only pornography is dishonesty.”

McKenna Taylor, watching her mother’s legacy reframed, said the experience changed her perspective on adult cinema:

“It wasn’t about redoing what she did. It was about letting her story evolve into something healing.”

And Johnnie Keyes, ever the philosopher, offered perhaps the most poetic summary:

“We weren’t making a dirty movie. We were finishing a prayer that started in 1972.”

The Film’s Reception and Cultural Resonance

When The New Behind the Green Door premiered, it divided audiences much as its predecessor had.

Mainstream critics mostly ignored it, but those who saw it recognized its ambition. A Letterboxd reviewer called it “a ghost story disguised as erotica.” Another described it as “the most introspective adult film ever made.”

Industry reviews were more precise:

- XBIZ: “A neo-noir confession that redefines the erotic gaze.”

- AVN: “Brooklyn Lee’s performance fuses physical and psychological honesty rarely seen in adult cinema.”

- Adult DVD Talk: “A brave, meditative remake—half mirror, half elegy.”

The film received AVN nominations for Best Actress and Best Director. For Brooklyn Lee, the project marked the summit of her brief but significant career; for Thomas, it was a farewell to filmmaking itself.

Years later, scholars of erotic cinema cite it alongside The Devil in Miss Jones and 9 Songs as one of the few works to treat sexuality as existential inquiry.

The Legacy: Between Celluloid and Memory

In the mythology of adult cinema, Behind the Green Door occupies a strange place—too artistic for pure pornography, too explicit for mainstream art. The 2013 remake inherits that duality and amplifies it.

By reimagining the original through female subjectivity, Paul Thomas and Brooklyn Lee achieved something rare: they turned the erotic into autobiography.

The film now circulates not as a best-seller but as a cult text, studied in film schools and discussed in feminist forums about representation. McKenna Taylor’s participation lends it documentary value; Johnnie Keyes’ appearance grounds it in continuity.

Its influence can be seen in later art-core works that use sensual imagery to explore trauma and identity—films by directors like Erika Lust, Jacky St. James, and Angie Rowntree, all of whom have cited Thomas as a bridge between eras.

Who Should Watch and What Fantasy It Serves

The New Behind the Green Door is not for casual viewing. It demands patience, attention, and a willingness to engage with erotic imagery as metaphor. Those seeking straightforward titillation will find it slow, cerebral, even frustrating.

But for viewers drawn to psychological eroticism, aesthetic sensuality, and cinema that questions its own gaze, it offers a singular experience.

It appeals to:

- Art-cinema enthusiasts who appreciate films that blur the boundary between adult and arthouse.

- Viewers curious about feminine agency and the evolution of desire in visual storytelling.

- Fans of the 1972 original who wish to see its myth reinterpreted through contemporary eyes.

The fantasy it serves is not carnal but existential—the fantasy of confession, of being fully seen and yet accepted. It’s the fantasy of liberation through recognition: of standing onstage, unmasked, and realizing the gaze can be gentle.

The Door That Never Closes

In the film’s final moments, Hope steps into daylight—her shadow merging with the city’s bustle. The camera lingers as she disappears into the crowd, and for a heartbeat, the screen glows green before fading to white.

It’s an image that encapsulates the entire philosophy of The New Behind the Green Door: desire as transformation, exposure as rebirth.

Paul Thomas once told an interviewer, “The original film opened a door. We just asked what happens when you walk through.”

That question remains its enduring gift.

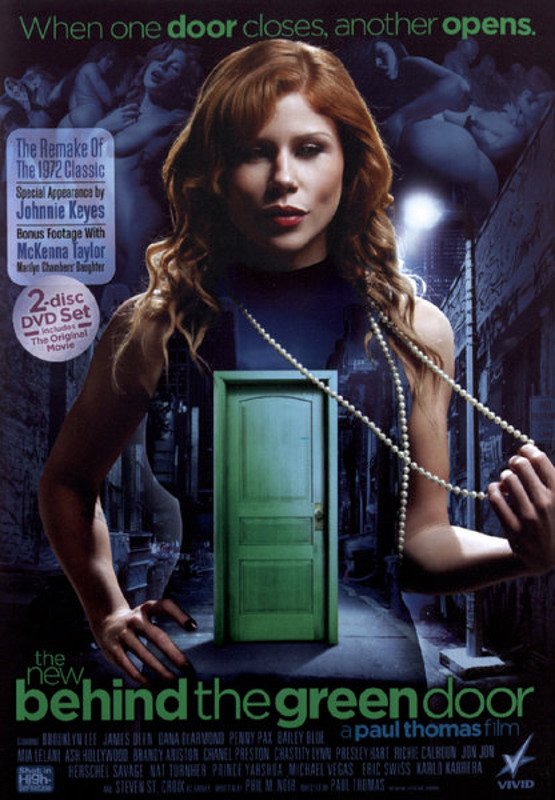

Official Title

The New Behind the Green Door

Also known as Behind the Green Door: The Next Chapter in some international catalog listings.

Studio & Production

- Studio: Vivid Entertainment

- Production Company: Vivid Features (a division of Vivid Entertainment Group)

- Executive Producer: Steven Hirsch

- Producer: Sam Hain

- Director: Paul Thomas

- Writer / Story: Phil M. Noir (pseudonym often used for Thomas’s screenplays)

- Director of Photography: Eddie Powell

- Production Design: Karl Edwards

- Editor: Mark Logan

- Music & Sound Design: Eddie Powell and Mark Nicholson

- Art Direction: Michael Vega

- Costume & Wardrobe: Delilah Caine

- Assistant Director: Hank Hoffman

- Makeup & Hair: Bree Daniels

- Production Manager: Kat Thomas

- Runtime: 132 minutes

- Format: High-definition digital (RED One camera, mastered in 1080p)

- Genre: Erotic Drama / Psychological Adult Feature

- Country: United States

- Language: English

Awards and Nominations

- 2013 AVN Awards:

- Winner – Best Actress (Brooklyn Lee)

- Nominated – Best Director (Paul Thomas)

- Nominated – Best Cinematography (Eddie Powell)

- Nominated – Best Art Direction

- Nominated – Best Screenplay

- 2013 XBIZ Awards:

- Nominated – Feature Movie of the Year

- Nominated – Best Actress (Brooklyn Lee)

- Nominated – Best Director (Paul Thomas)

Principle Cast

| Performer | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Brooklyn Lee | Hope | Central protagonist; a woman in search of identity and legacy. |

| James Deen | James | Hope’s volatile boyfriend; represents dependence and decay. |

| Richie Calhoun | Richie | Former lover turned catalyst for Hope’s initiation. |

| Chanel Preston | The Guide / Priestess | Initiates Hope into the Green Door ritual. |

| Steven St. Croix | The Host | Mysterious organizer of the Caligula Club. |

| Dana DeArmond | Eden | Symbolic figure of temptation and empathy within the club. |

| Nat Turnher | The Warrior | Performer in the ritual sequence; embodiment of strength. |

| Jon Jon | The Witness | Secondary ritual performer; mirrors compassion. |

| Prince Yahshua | The Healer | Performer symbolizing transcendence and acceptance. |

| McKenna Taylor | Cameo / The Daughter’s Echo | Daughter of Marilyn Chambers; meta-appearance linking films. |

| Johnnie Keyes | Himself (Cameo) | Original 1972 star; appears as silent observer in audience. |

| Herschel Savage | The Pawnbroker | Brief appearance offering prophetic dialogue early in film. |

| Penny Pax | Club Performer | Featured in symbolic stage sequence. |